As several of my colleagues have gleefully remarked this week, I’ve officially turned to the dark side and published some research on theropods, and theropod FEEDING at that, thus making me a Real Palaeontologist™ after more than a decade at this. Anyway, read on for some non-ankylosaury research, if you dare!

My very good friend and colleague Angelica Torices at the Universidad de La Rioja in Spain asked me to collaborate with her on a project she had been working on with UAlberta BSc student Ryan Wilkinson on theropod teeth. Angelica had been collecting data on theropod tooth microwear for many years, and was working with Ryan to incorporate that dataset with biomechanical models of theropod feeding. Since I’d worked with finite element analyses previously in my work on ankylosaur tail club biomechanics, I was brought on board to help oversee some of that work and to help interpret the results. The paper’s had some really nice coverage online already so I’ll recommend checking out the Washington Post and Discover for a summary of our work. However, I thought it would be fun to highlight a few videos that bring to life some of what we talk about in the paper.

Angelica’s work on theropod tooth microwear showed that teeth from all different sorts and sizes of theropods in both Canada and Spain had similar patterns – a set of scratches parallel to the denticles, a set of oblique scratches all oriented at about the same angle, and very few pits compared to scratches. This suggested that there were two main movements that formed the scratches: 1) a downward bite into prey that formed the parallel scratches, and 2) a pulling-back movement that formed the oblique scratches.

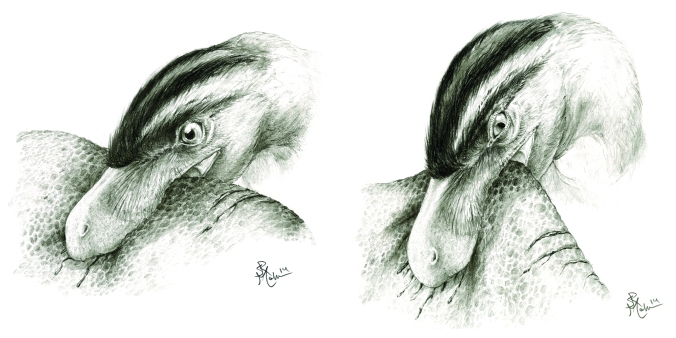

(Thank you Sydney Mohr for this beautiful reconstruction of a Saurornitholestes chowing down on a nice piece of dinosaur meat!)

(Thank you Sydney Mohr for this beautiful reconstruction of a Saurornitholestes chowing down on a nice piece of dinosaur meat!)

If you’d like to see puncture-and-pull feeding in action, here’s a video of a Komodo dragon employing the technique on a deer carcass. Warning: it’s gross, guts and blood are voluminous.

Komodo dragons don’t really try to gnaw on bones while they’re eating, either defleshing the skeleton while avoiding bones, or simply swallowing chunks of the body whole. Stick some feathers on that dragon and have it stand up on its hind legs, and this is probably close to what it looked like when many theropods fed on their prey, based on the microwear data.

In contrast, here’s a pack of hyaenas stripping a carcass. This one’s slightly less gross but still involves insides on the outside.

You can see there’s a lot more nibbling with the front teeth, and turning the head to the side to make use of the shearing carnassials. Gnawing and chewing on bones tends to produce more pits on mammalian carnivore teeth. The absence of pits on theropod teeth might be because they shed their teeth regularly, unlike mammals, but it also probably means many theropods weren’t intentionally chewing on bones much of the time.

Anyway, this was a fun project to work on, so, thanks Angelica for inviting me to be part of it! Here’s a picture of us (and Boo, official Science Chihuahua of the Torices household) right after we submitted the revised version of this paper while I was visiting Spain last November. You can follow more of Angelica’s research on Twitter and Facebook!

Pingback: I Know Dino: The Big Dinosaur Podcast | A site about dinosaurs | I Know Dino Podcast Show Notes: Nipponosaurus (Episode 180)

Pingback: I Know Dino: The Big Dinosaur Podcast | A site about dinosaurs | This Week in Dinosaur News: a new well preserved dinosaur and hundreds of new tracks from China, theropod feeding, and more

Pingback: Fossil Friday Roundup: May 4, 2018

Pingback: I Know Dino Podcast Present Notes: Nipponosaurus (Episode 180) - Street How

Pingback: I Know Dino Podcast Present Notes: Nipponosaurus (Episode 180) - 1 Cat 2 Dogs